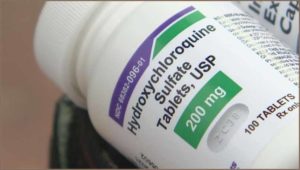

There has been a lot of controversy about the use of Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) as a treatment of COVID-19. This is an old antiviral medication, in use for more than 60 years, and considered safe for daily use even during pregnancy, yet doctors have risked their careers to use it for patients with COVID-19.

There has been a lot of controversy about the use of Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) as a treatment of COVID-19. This is an old antiviral medication, in use for more than 60 years, and considered safe for daily use even during pregnancy, yet doctors have risked their careers to use it for patients with COVID-19.

Today, in many parts of the US, pharmacies refuse to fill prescriptions; claims have been made that it is safe, unsafe, deadly, wonderful, terrible, or useless. The reasons for all this go deep into politics and the problem that an emergency vaccine can only be approved if no acceptable treatment or prevention is available.

The Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has issued warnings to doctors and pharmacies. In June and July, 2020, the FDA decided that HCQ should no longer be used to treat patients with Covid 19 because it is too dangerous. It is not considered too dangerous, however, for treatment of lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or malaria.

The American Medical Association issued a statement in April 2020 that I would find insulting were I a doctor. After noting that doctors are at the forefront of any emergency medical situation, they claimed that doctors have been buying up HCQ and azithromycin (specifically) and hoarding them for their own families and patients. They suggested that pharmacists should question or even refuse such prescriptions, since this may deplete the market; there is no suggestion that perhaps production of these drugs could be increased to meet the perceived need.

Below, we will let the research itself talk about the urgent topic of its use for treatment and/or prevention of COVID-19.

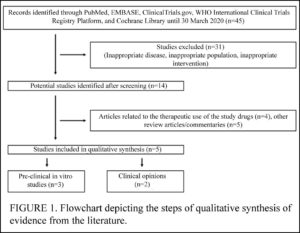

Shah et al (March 2020) reviewed the few studies on the use of HCQ and the similar CQ for COVID-19 published by March, 2020. In spite of acknowledging that HCQ has a good safety profile, the authors conclude that the drug should NOT be used against COVID-19, claiming it might cause a “false sense of protection among the common masses.” More . . .

Shah et al (March 2020) reviewed the few studies on the use of HCQ and the similar CQ for COVID-19 published by March, 2020. In spite of acknowledging that HCQ has a good safety profile, the authors conclude that the drug should NOT be used against COVID-19, claiming it might cause a “false sense of protection among the common masses.” More . . .

![]()

Singh et al (March 2020) reviewed only 2 studies, concluding that HCQ and the related CQ are worth fast-tracking clinical trials for treatment of Covid-19.

Singh et al (March 2020) reviewed only 2 studies, concluding that HCQ and the related CQ are worth fast-tracking clinical trials for treatment of Covid-19.

They also noted that (in India) HCQ is approved for diabetes — and diabetics are at high-risk for COVID-19 mortality. More . . .

![]()

Garcia-Cremades et al (August 2020) attempted to pinpoint the best dose of HCQ both for treatment and for clinical trials, while avoiding the heart QT problem of higher doses.

Garcia-Cremades et al (August 2020) attempted to pinpoint the best dose of HCQ both for treatment and for clinical trials, while avoiding the heart QT problem of higher doses.

The dosage appears to be 600 mg HCQ twice a day for 10 days, but even 200 mg HCQ twice a day for 5 days is better than nothing.

More . . .

![]()

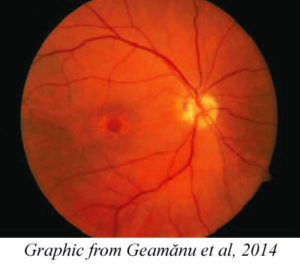

Marmor (May 2020) says that “the evidence to date indicates that extreme doses do accelerate retinal toxicity, but with a probable time course of many months rather than days.”

Marmor (May 2020) says that “the evidence to date indicates that extreme doses do accelerate retinal toxicity, but with a probable time course of many months rather than days.”

During this time of crisis, he concludes, ophthalmologists should be reassuring physicians and the public that retinopathy is not a serious concern in CQ or HCQ usage for COVID-19. Several other papers about this connection are also linked. More . . .

![]()

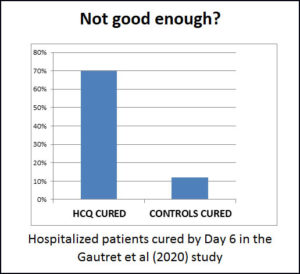

Gbinigie & Frie (April 2020) reviewed three studies – two from China and one from France. China began to recommend HCQ as a treatment based on the first Chinese study. The other Chinese study (of only 30 people) could not show a difference between treatment and control groups, but they were using a very small dosage of HCQ. The French study showed that 70% of the treatment group recovered in 6 days, while only 12% of the “control” group recovered.

Gbinigie & Frie (April 2020) reviewed three studies – two from China and one from France. China began to recommend HCQ as a treatment based on the first Chinese study. The other Chinese study (of only 30 people) could not show a difference between treatment and control groups, but they were using a very small dosage of HCQ. The French study showed that 70% of the treatment group recovered in 6 days, while only 12% of the “control” group recovered.

Nevertheless, Gbinigie et al conclude there is insufficient evidence to support the use of CQ or HCQ for treatment of Covid-19. More . . .

![]()

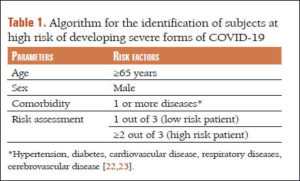

Giammaria & Pajewski (June 2020) — their paper’s name is the question, “Can early treatment of patients with risk factors contribute to managing the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Giammaria & Pajewski (June 2020) — their paper’s name is the question, “Can early treatment of patients with risk factors contribute to managing the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Basically, their answer is YES.

Only about 20% of patients with COVID-19 develop serious symptoms, which seem to take about a week to come on, giving time to identify those at risk and treat them with antiviral medications. More . . .

![]()

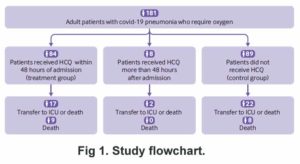

Mahevas et al (May 2020) studied patients who had all developed pneumonia and needed oxygen.

Mahevas et al (May 2020) studied patients who had all developed pneumonia and needed oxygen.

The dose of HCQ used was 600 mg per day, but without zinc or antibiotic. The authors concluded that for patients in a hospital needing and on oxygen, HCQ doesn’t do much.

The authors claimed no conflicts of interest, but when the BMJ investigated, there were quite a few.. More . . .

![]()

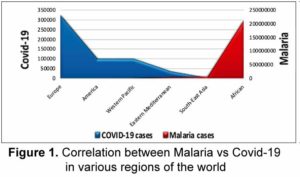

Meo et al (April 2020) concluded their findings support the hypothesis that HCQ can both treat and prevent Covid-19.

Meo et al (April 2020) concluded their findings support the hypothesis that HCQ can both treat and prevent Covid-19.

![]()

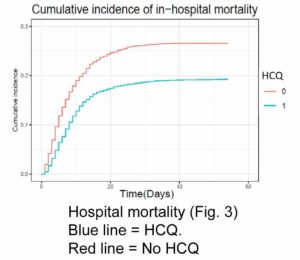

Catteau et al (2020) compared patients receiving HCQ for 5 days to patients receiving only supportive care.

Catteau et al (2020) compared patients receiving HCQ for 5 days to patients receiving only supportive care.

Patients receiving HCQ were less likely to die. The recommended dose of HCQ was 2400 mg over 5 days, or about 480 mg per day.

![]()

Abd-Elsalam et al (Oct, 2020) compared two groups of hospitalized patients. One group of 97 patients received “standard” care and the other 97 received that plus 400 mg/day HCQ (without zinc).

Abd-Elsalam et al (Oct, 2020) compared two groups of hospitalized patients. One group of 97 patients received “standard” care and the other 97 received that plus 400 mg/day HCQ (without zinc).

Although 20% more of the HCQ group recovered, this was not statistically significant.

![]()

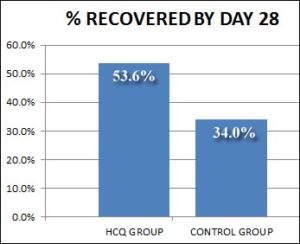

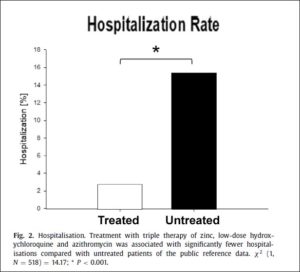

Derwand, Scholz & Zelenko (Dec. 2020) demonstrated a dramatic reduction in serious illness when people at risk were treated early with HCQ, zinc, and the antibiotic azithromycin. They provide the protocol they used. Download it if you are a doctor, or — if you are the patient — dowload and discuss it with your doctor to be ready just in case you get sick.

Derwand, Scholz & Zelenko (Dec. 2020) demonstrated a dramatic reduction in serious illness when people at risk were treated early with HCQ, zinc, and the antibiotic azithromycin. They provide the protocol they used. Download it if you are a doctor, or — if you are the patient — dowload and discuss it with your doctor to be ready just in case you get sick.

![]()

Meryl Ness, MD (2020) reviews the SOLIDARITY and RECOVERY clinical trials that concluded Hydroxychloroquine is dangerous and useless in Covid. She shows how they used potentially fatal doses to do so. In other times and places, this would have been called murder.

Meryl Ness, MD (2020) reviews the SOLIDARITY and RECOVERY clinical trials that concluded Hydroxychloroquine is dangerous and useless in Covid. She shows how they used potentially fatal doses to do so. In other times and places, this would have been called murder.